It’s been a while, two years since I last posted on this site. Hopefully, we’re on the path out of a pseudo populism that was never about real populism but more about how to bulk up the stock market and pretend to appease the working class, who hasn’t made any real strides forward since the 1990s. Both sides bought the lie. I’ve been doing more reading than painting this year. As I began writing this, the woman who has the ability to “ascertain” the formal transition process for President-elect Biden, finally agreed to do so. That’s something I hadn’t ever paid attention to before. It’s all about the transfer of money to the new administration.

I’ve read moving and inspirational journals from artists working outside their inner city studios since this plague began. Many from blogs that I follow, other creative outpourings from Art Papers, published here in Atlanta. Lucky is the artist having a city studio and a country hideout – or a residency. And although the art world has done its share for inclusion this year, I doubt much will change for the average person, no matter their race, color or gender. We still have housing affordability issues and rampaging development with a loss of tree canopy that threatens to exacerbate stormwater issues like runoff and flooding here in metro Atlanta, and across the country. As environmental activists, we encourage local officials to strengthen tree ordinances, with increased pervious surface percentages. However, pushing that through also requires a larger civic involvement; tenacious pressure that has to be ongoing. Everything ends up being political.

I continue to paint, but my work has always been informed by a focus on place and how the natural world is often sidelined, especially in a large and thriving city. Right now I’m distracted by the election process as well as trying to survive the pandemic. I’ve been trying to figure out where this election went wrong, even though my side has ostensibly won. Populism as a descriptor of our current situation has flipped from its origins as a farmers’ collective, as this provocative C-Span podcast with author Thomas Frank & right wing journalist Chris Caldwall discuss during the National Book Festival this September. Eric Deggans is the moderator who keeps things on track.

As the Kansas Historical Society suggests, during the 1880s to 1890s “The Farmers’ Alliance movement was growing in the South and Midwest. The group promoted higher prices for produce and felt that the government’s responsibility was to represent farmers rather than big business. In their view, railroads, banks, and other businesses received more support from government.“

Soybean, dairy and pig farmers who voted for Trump in 2016 thought he’d have their backs as he blithely promised in his ‘America First’ mantra during his campaign, echoing The People’s Party similar complaints about their government in the late 1800s. Instead, Trump’s tariffs on China backfired. Farmers have suffered greatly during this administration, even as smaller farms were on the brink of failure before his tenure. This NY Times article from June outlines the decline due to the badly timed tariffs; “Overall sales of American farm goods to China remained deeply depressed, dropping to $9.3 billion in 2018 from $19.6 billion in 2017 as the trade war escalated, before picking up to about $14 billion last year.”

Why does the working class keep voting against their own interests? And more to the point, what did they see in the failed businessman Trump? I think they overlooked his failures and merely bought the showman. Last year a friend gave me Hate, Inc. by journalist Matt Taibbi, which makes an excellent point about the chasm between those who voted for DT and the rest of us. Because he notes these two as better than the rest of the professional pundits, I recently bought a couple of Thomas Frank’s books. I also dug up the article that Taibbi mentions that professor Joan C. Williams published in the Harvard Business Review back in 2016 a month after those election results. Williams is the founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law. Her newest book is White Working Class: Overcoming Class Cluelessness in America. An excerpt from the Harvard Business Review piece states the following:

Michèle Lamont, in The Dignity of Working Men, also found resentment of professionals — but not of the rich. “[I] can’t knock anyone for succeeding,†a laborer told her. “There’s a lot of people out there who are wealthy and I’m sure they worked darned hard for every cent they have,†chimed in a receiving clerk. Why the difference? For one thing, most blue-collar workers have little direct contact with the rich outside of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. But professionals order them around every day. The dream is not to become upper-middle-class, with its different food, family, and friendship patterns; the dream is to live in your own class milieu, where you feel comfortable — just with more money. “The main thing is to be independent and give your own orders and not have to take them from anybody else,†a machine operator told Lamont. Owning one’s own business — that’s the goal. That’s another part of Trump’s appeal.

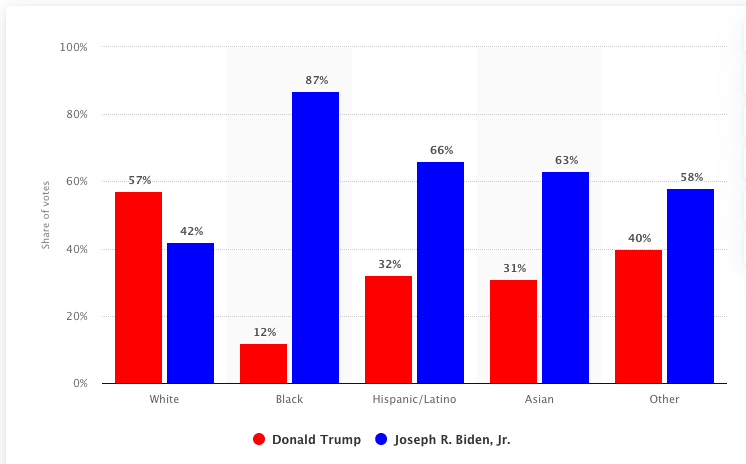

So maybe that partially answers why the man was able to steal his first election. But the issue of 70 million mostly white voters still believing in him for a second run speaks more to continuing racial issues in the country than anything else.

It’s almost unbelievable but not quite, that the state of Georgia could be responsible for handing the Senate back to the Democratic Party. When my ex-husband and I decided to move back from Canada to the states in the summer of 1976, I researched which cities had the most likely future growth and chose Atlanta. He left soon afterwards, but the city has never disappointed.

After having been involved for the last decade with my community and local government here, much of which has included a crash course on zoning and urban planning, I’ve realized that the African American contingent, and especially women of color, is what makes Atlanta and environs such a unique place to live. This demographic comes out swinging to protect their neighborhoods from over-development and they value the health of our environment.

Women taking the lead in progressive movements is nothing new, throughout history we’ve been at the front lines. I met Medea Benjamin in San Francisco at the outset of the Iraq War, protesting with her band of Code Pink activists and engaging in all sorts of civil disobedience. She’s still at it, fighting for justice and human rights.

Organizers all over the world have known for centuries that the masses hold the most power; disobedience and civil resistance works. Marching in the streets is most effective combined with strategic objectives. It helps to know one’s elected officials to be able to call on them during crises. Even on the local level, developing a good relationship with one’s county commissioner or city councilwoman can be critical and make the difference in keeping bad developers beyond the gates.

This week’s New Yorker has a great article mostly focused on Erica Chenoweth, the political scientist and professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Some valuable excerpts:

“The study of civil resistance… is in large part the study of how movements can win “defectionsâ€â€”how they can turn obedient subjects of the regime into allies of the disobedient majority.

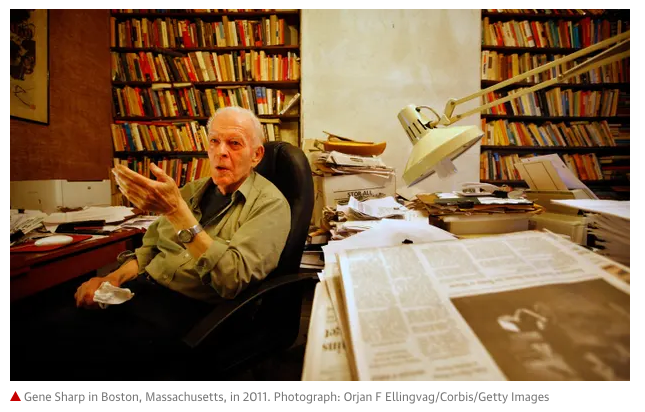

In 1973, the political scientist Gene Sharp published “The Politics of Nonviolent Action†…In the sixteenth century, Iroquois women won political rights within their tribe through a coördinated succession of actions: refraining from sex and childbirth, striking when it came time to harvest crops, refusing to make moccasins for male soldiers. In the Iranian Revolution of 1979, some of the most decisive gains against the Shah came from acts of bureaucratic slow-walking, and from employees at nationalized oil fields working at half speed. In the American imagination, an uprising looks like a throng. In the Sharpian tradition, the winning combination of tactics may look like an absence—or, to the untrained eye, like nothing at all.

While mostly male friends were anguishing about blood running in the streets or increased violence after an election that didn’t mollify the Proud Boys and their ilk, I kept thinking about historical wins by ‘the people’ against tyranny. So many of us forget that our individual power to affect change can be a reality – and en masse, it’s amplified. If the internet and social media has garnered eyes and the cable/tv/streaming industry has made monied stickiness its motivating force, the forgotten message is to harness the power of the masses to make our officials accountable. Activists know this without having data but having it helps.

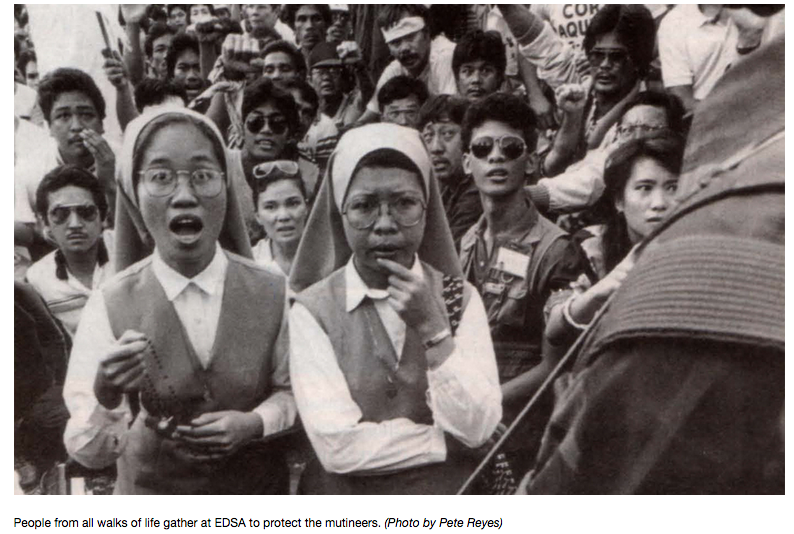

In 2011, Chenoweth and Stephan published their findings in a book called “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.†It included detailed narrative case studies in which the authors hypothesized about why, say, the Philippine People Power movement of 1986 achieved its goals whereas the Burmese uprising of 1988 did not. (In Burma, activists over-relied on “methods of concentration, such as election rallies and protests,†leaving themselves vulnerable to state repression. The movement in the Philippines alternated rallies with strikes and boycotts; it also drew the participation of a wide array of civil-society leaders, including clergy and teachers, many of whom eventually turned against the regime.)

In September of 2000, Slobodan Milosevic, who had been the dictator of Serbia for more than a decade, attempted to falsify election results in order to stay in power. In response, a student-led movement called Otpor coördinated a variety of tactics—highway blockades, subversive street theatre, a coal miners’ strike. The resistance was widely perceived as nonviolent and legitimate, and it grew quickly, gaining support among Serbs of every age and from all parts of the country. A Serbian policeman, ordered to shoot into a crowd of protesters, held his fire; he later told journalists that, given the cross-section of people present, he couldn’t rule out the possibility that one of them was his child. By early October, Milosevic had no choice but to leave office.”

It appears now that Mr. Trump will have no choice but to concede, whether he does that directly or indirectly by leaving office. 2021 will be a good year.